Flawfinder

Flawfinder searches through C/C++ source code looking for potential security flaws. To run flawfinder, simply give flawfinder a list of directories or files. For each directory given, all files that have C/C++ filename extensions in that directory (and its subdirectories, recursively) will be examined. Thus, for most projects, simply give flawfinder the name of the source code’s topmost directory (use ‘‘.’’ for the current directory), and flawfinder will examine all of the project’s C/C++ source code. Flawfinder does not require that you be able to build your software, so it can be used even with incomplete source code. If you only want to have changes reviewed, save a unified diff of those changes (created by GNU “diff -u” or “svn diff” or “git diff”) in a patch file and use the −−patch (−P) option.

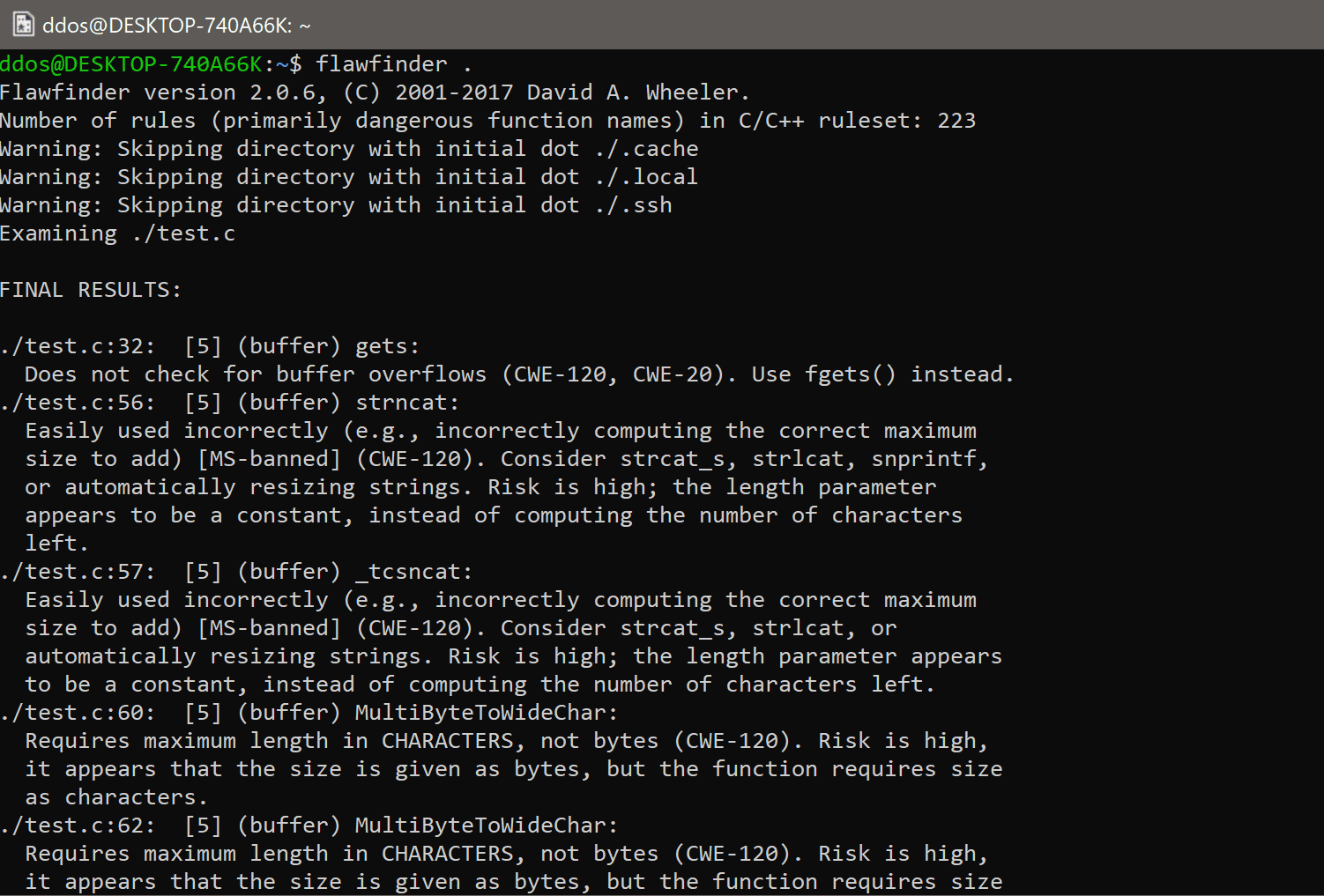

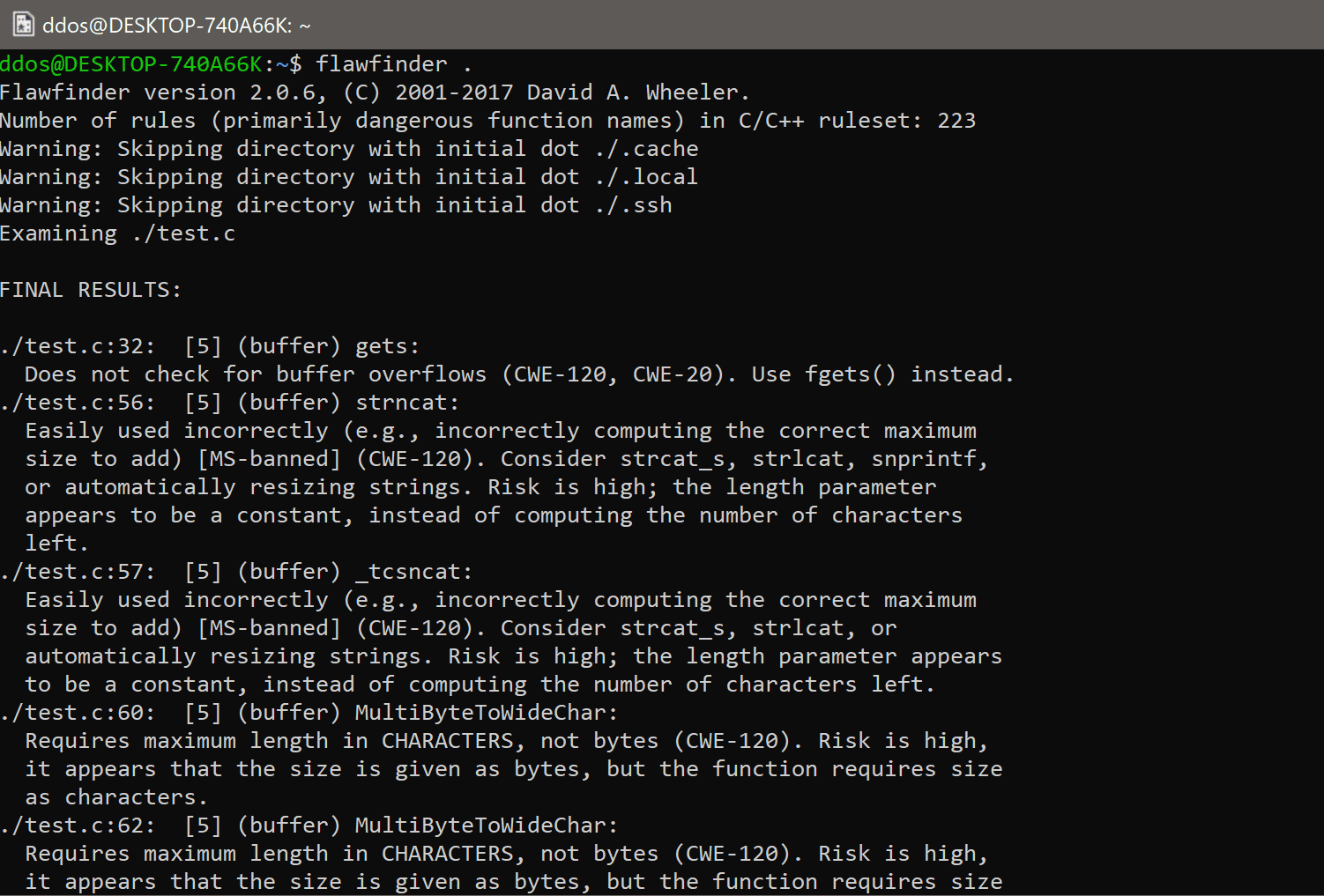

Flawfinder will produce a list of ‘‘hits’’ (potential security flaws, also called findings), sorted by risk; the riskiest hits are shown first. The risk level is shown inside square brackets and varies from 0, very little risk, to 5, great risk. This risk level depends not only on the function but on the values of the parameters of the function. For example, constant strings are often less risky than fully variable strings in many contexts, and in those contexts, the hit will have a lower risk level. It knows about gettext (a common library for internationalized programs) and will treat constant strings passed through gettext as though they were constant strings; this reduces the number of false hits in internationalized programs. Flawfinder will do the same sort of thing with _T() and _TEXT(), common Microsoft macros for handling internationalized programs. It correctly ignores text inside comments and strings. Normally flawfinder shows all hits with a risk level of at least 1, but you can use the −−minlevel option to show only hits with higher risk levels if you wish. Hit descriptions also note the relevant Common Weakness Enumeration (CWE) identifier(s) in parentheses, as discussed below. Flawfinder is officially CWE-Compatible. Hit descriptions with “[MS-banned]” indicate functions that are on the banned list of functions released by Microsoft; see http://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/bb288454.aspx for more information about banned functions.

How does Flawfinder Work?

Flawfinder works by using a built-in database of C/C++ functions with well-known problems, such as buffer overflow risks (e.g., strcpy(), strcat(), gets(), sprintf(), and the scanf() family), format string problems ([v][f]printf(), [v]snprintf(), and syslog()), race conditions (such as access(), chown(), chgrp(), chmod(), tmpfile(), tmpnam(), tempnam(), and mktemp()), potential shell metacharacter dangers (most of the exec() family, system(), popen()), and poor random number acquisition (such as random()). The good thing is that you don’t have to create this database – it comes with the tool.

It then takes the source code text, and matches the source code text against those names, while ignoring text inside comments and strings (except for flawfinder directives). Flawfinder also knows about gettext (a common library for internationalized programs), and will treat constant strings passed through gettext as though they were constant strings; this reduces the number of false hits in internationalized programs.

Flawfinder produces a list of “hits” (potential security flaws), sorted by risk; by default, the riskiest hits are shown first. This risk level depends not only on the function but on the values of the parameters of the function. For example, constant strings are often less risky than fully variable strings in many contexts. In some cases, flawfinder may be able to determine that the construct isn’t risky at all, reducing false positives.

It gives better information – and better prioritization – than simply running “grep” on the source code. After all, it knows to ignore comments and the insides of strings, and it will also examine parameters to estimate risk levels. Nevertheless, flawfinder is fundamentally a naive program; it doesn’t even know about the data types of function parameters, and it certainly doesn’t do control flow or data flow analysis (see the references below to other tools, like SPLINT, which do deeper analysis). I know how to do that, but doing that is far more work; sometimes all you need is a simple tool. Also, because it’s simple, it doesn’t get as confused by macro definitions and other oddities that more sophisticated tools have trouble with. It can analyze the software that you can’t build; in some cases, it can analyze files you can’t even locally compile.

Installation

pip install flawfinder

Usage

Copyright (C) 2021 david-a-wheeler

Source: https://github.com/david-a-wheeler/