The SideWinder Advanced Persistent Threat (APT) group, also known as T-APT-04 or RattleSnake, has been a relentless actor in the global cyber espionage landscape since its emergence in 2012. Though initially recognized for its attacks in South and Southeast Asia, SideWinder’s latest campaign marks a significant expansion in both scope and sophistication. A recent report from Kaspersky researchers, Giampaolo Dedola and Vasily Berdnikov, sheds light on this group’s evolving strategies and new tools, with particular focus on its increasing global reach and technical expertise.

Originally, SideWinder focused on military and government entities in Pakistan, Sri Lanka, China, and Nepal. Over the years, this group has been responsible for an impressive number of cyberattacks, using tools and techniques that, on the surface, appear low-skilled. As Dedola and Berdnikov noted, “The group may be perceived as a low-skilled actor due to the use of public exploits, malicious LNK files and scripts as infection vectors.” However, this perception changes upon closer analysis of their operations.

In a recent turn of events, SideWinder’s campaigns have expanded beyond their traditional targets. The report highlights new waves of attacks against high-profile entities and strategic infrastructure in the Middle East and Africa. This shift signifies not only geographic expansion but also the targeting of sectors such as logistics, telecommunications, oil trading companies, and universities. Diplomatic entities in Afghanistan, France, China, India, and Indonesia have also been affected.

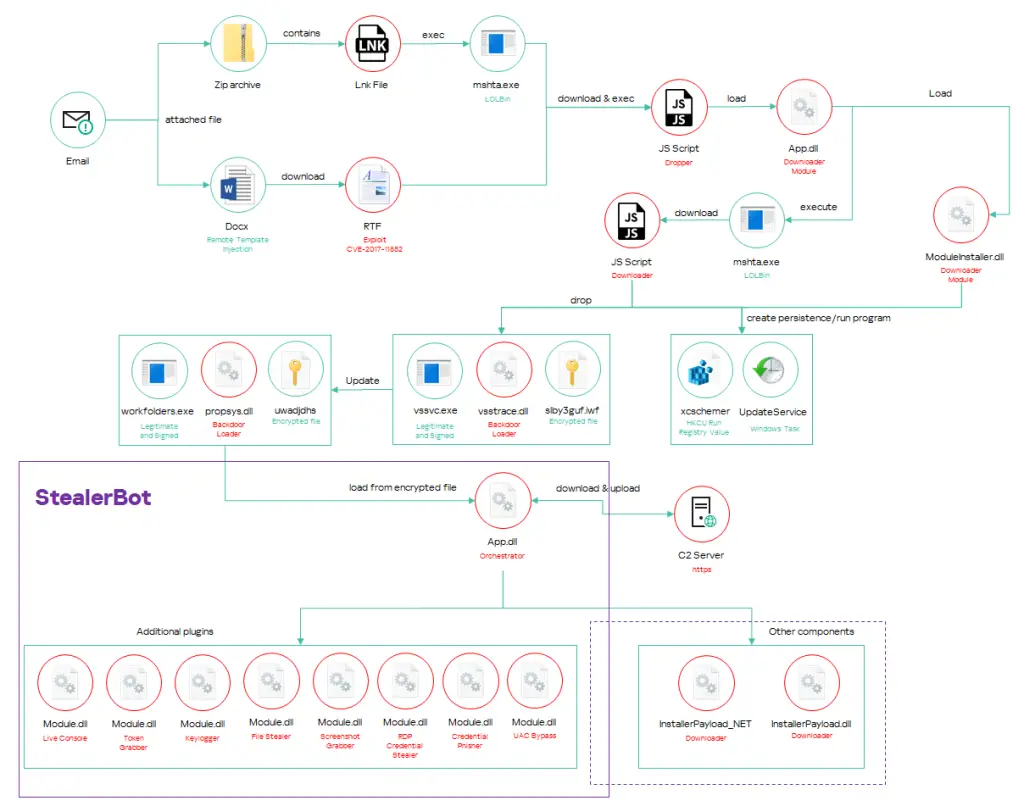

A standout revelation in the report is SideWinder’s use of an advanced modular post-exploitation tool called “StealerBot.” This toolkit is specifically designed for espionage and has been observed as the primary post-compromise tool in many of SideWinder’s recent operations. StealerBot’s capabilities include password theft, keylogging, capturing screenshots, and even executing a reverse shell to allow attackers to control compromised machines remotely.

One of StealerBot’s key features is its stealthiness. It never writes components to the filesystem, instead loading them directly into memory. The researchers noted, “We never observed any of the implant components on the filesystem. They are loaded into memory by the Backdoor loader module,” making detection and analysis significantly more challenging for defenders.

SideWinder continues to rely heavily on spear-phishing to initiate its attack chain. The typical vector involves sending a malicious Microsoft OOXML document or a ZIP file containing a LNK file, which triggers a multi-stage infection chain. The malicious payload eventually leads to the installation of the StealerBot tool. A hallmark of this method is its use of remote template injection to download an RTF file that exploits CVE-2017-11882.

In addition to this tried-and-tested method, the attackers have employed more sophisticated anti-analysis techniques, including checks for virtualized environments and obfuscated strings that are decoded during runtime, making static analysis of the malware difficult.

The infrastructure used by SideWinder has been tracked across various regions, with many domains attempting to mimic legitimate government and military entities. For instance, domains like “nextgen.paknavy-govpk.net” attempt to appear as though they belong to official entities in Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and Djibouti. These tactics are consistent with SideWinder’s past behavior, further solidifying its attribution.

Kaspersky’s analysis attributes this campaign to SideWinder with “medium/high confidence,” based on the overlap of techniques, domains, and malware components with those observed in the group’s earlier activities.

The introduction of new tools like StealerBot and their expansion into new territories suggests that SideWinder’s influence on the cyber espionage stage will continue to grow. As Dedola and Berdnikov highlight, “Despite years of observation and study, knowledge of their post-compromise activities remains limited,” underscoring the ongoing challenge of tracking and mitigating this persistent threat.