On January 26, security researchers at Bitdefender, an Internet security company, have found “Hide ‘N Seek” (HNS) a new IoT botnet. Experts said that the botnet first appeared on January 10, 2018. Now, HNS has been expanded from 12 to 14,000 units.

Bogdan Botezatu, a senior cyber threat analyst at Bitdefender, pointed out that unlike other IoT botnets that have emerged in recent weeks, HNS is not another variant of Mirai, but rather akin to Hajime.

Botezatu indicated that HNS is the second known IoT botnet with a peer-to-peer (P2P) architecture following the Hajime botnet. However, for Hajime, P2P functions are based on the BitTorrent protocol, while HNS has a custom built P2P communication mechanism.

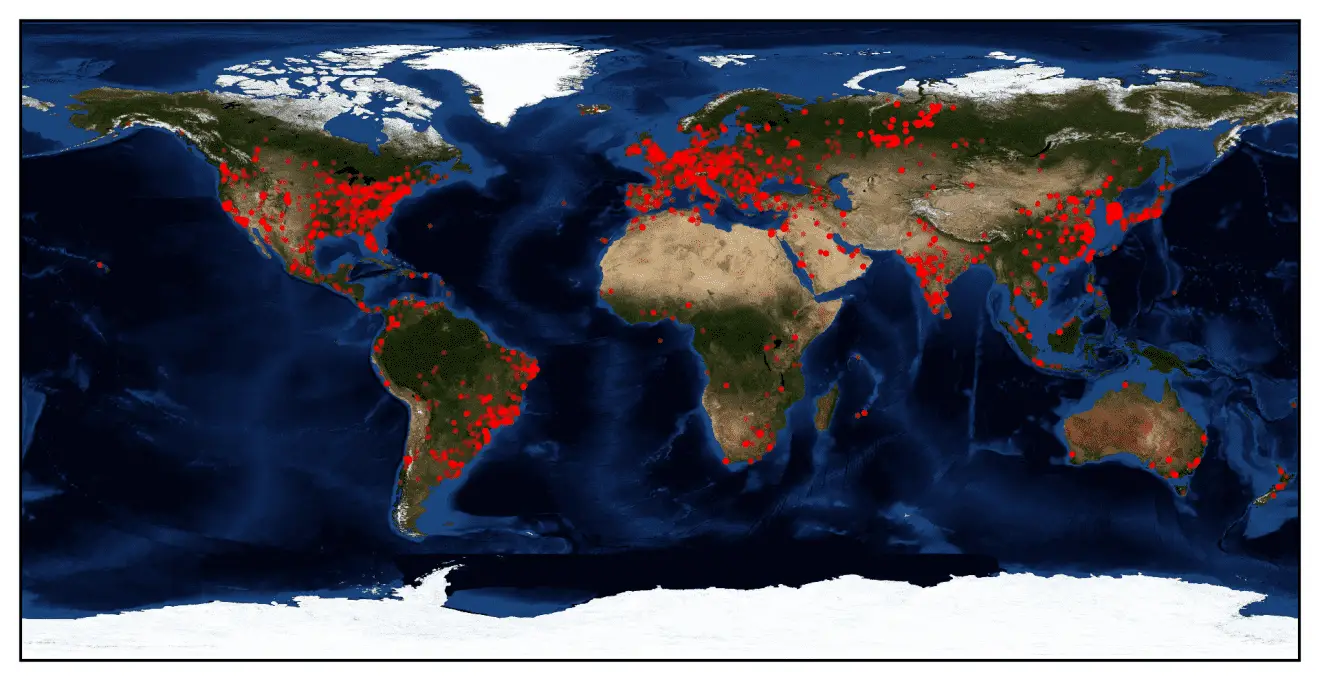

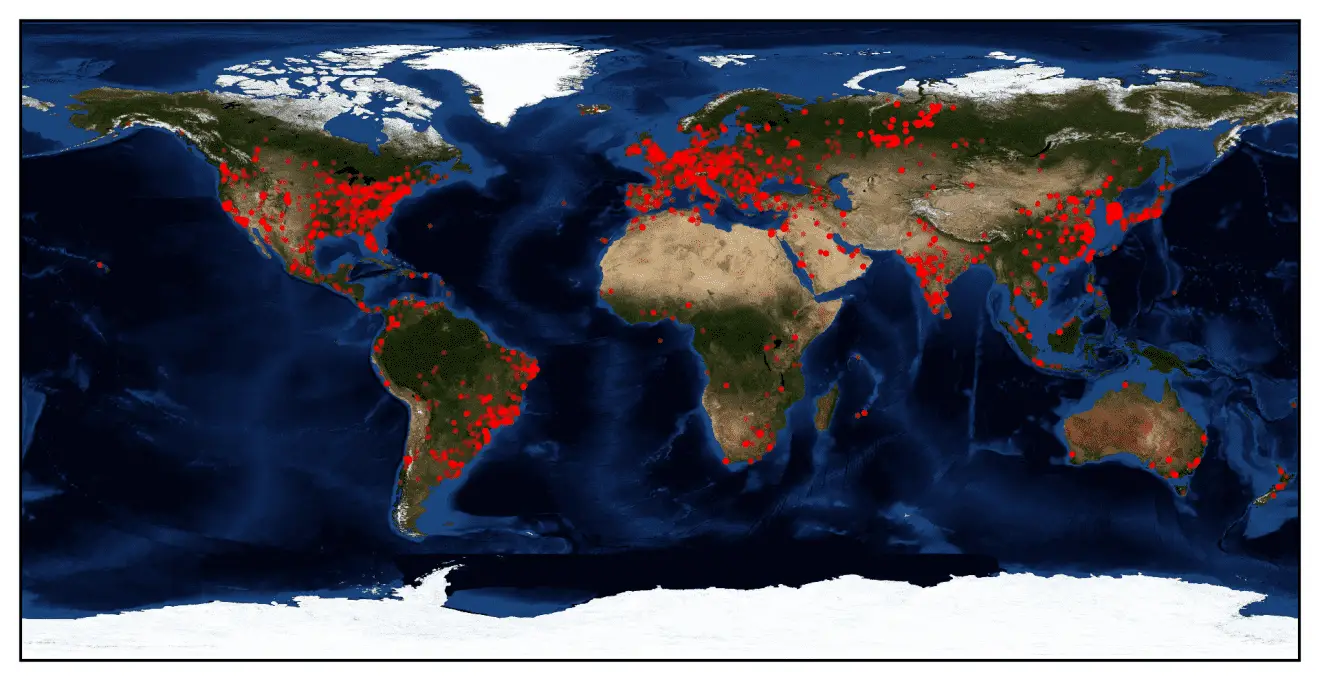

Botezatu chart analysis in the report pointed out that each HNS bot contains another IP bot list. This list can be updated in real-time with the size of the botnet and the number of bots.

HNS will pass instructions and commands to each other, similar to the basis of P2P protocol. Bottezza shows that an HNS bot can receive and execute many command types such as data breaches, code execution, and interfering device operations.

Surprisingly, researchers did not find DDoS attacks in HNS, meaning that HNS was designed to be deployed as a proxy network in much the same way that most IoT botnets were weaponized in 2017. Earlier, DDoS attacks attracted so much attention that many botnets disappeared.

The HNS botnet initiates dictionary brute-force attacks on devices that have open Telnet ports, a propagation mechanism that, like its unique P2P zombie management protocol, is highly customizable.

The bot features a worm-like spreading mechanism that randomly generates a list of IP addresses to get potential targets. It then initiates a raw socket SYN connection to each host in the list and continues communication with those that answer the request on specific destination ports (23 2323, 80, 8080). Once the connection has been established, the bot looks for a specific banner (“buildroot login:”) presented by the victim. If it gets this login banner, it attempts to log in with a set of predefined credentials. If that fails, the botnet attempts a dictionary attack using a hardcoded list.

Once a session is established with a new victim, the sample will run through a “state machine” to properly identify the target device and select the most suitable compromise method. For example, if the victim has the same LAN as the bot, the bot sets up TFTP server to allow the victim to download the sample from the bot. If the victim is located on the internet, the bot will attempt a specific remote payload delivery method to get the victim to download and run the malware sample. These exploitation techniques are preconfigured and are located in a memory location that is digitally signed to prevent tampering. This list can be updated remotely and propagated among infected hosts.

But thankfully, HNS, like all IoT malware, cannot build persistence on an infected device, meaning that the malware is automatically deleted when the device restarts. This also frees stakeholders to manage the botnet around the clock because the creators keep monitoring the botnet to ensure continued access to the new bot.

Since HNS is a new IoT botnet, its creators will explore new ways of spreading and bot management technologies and are therefore in a state of constant change. Experts said that the botnet consisting of 14,000 bots should not be overlooked because botnets that generally have some “lethality” do not need tens of thousands of bots at all, and four or five thousand is enough.

Source: bleepingcomputer