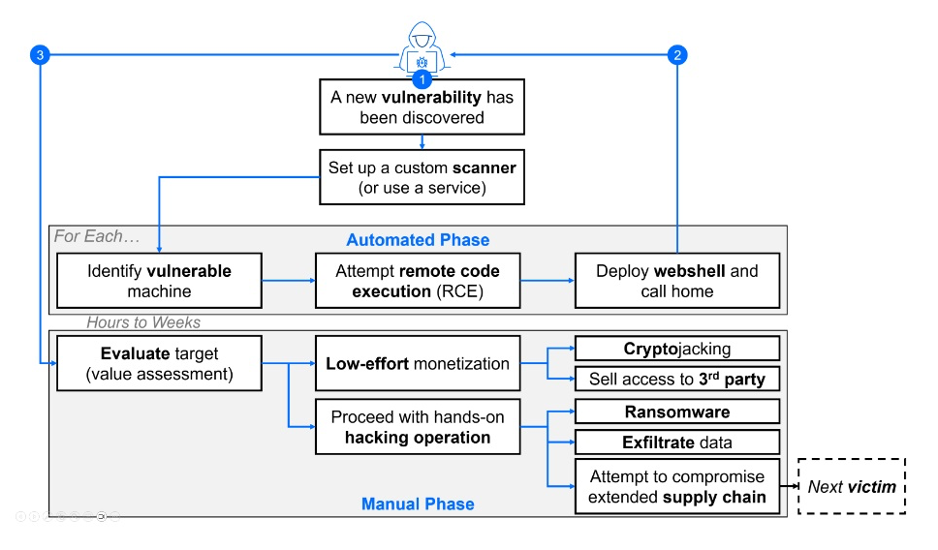

The ransomware attack - from vulnerability discovery to ransomware deployment | Image: Bitdefender

A recent report from Bitdefender highlights how Medusa has not only continued its relentless attacks but has also established a unique online presence on both the dark web and the surface web, making it a ransomware group to watch closely.

What sets Medusa apart from other ransomware groups is its use of a name-and-shame blog on the surface web, where it posts information about its victims alongside the traditional dark web leak sites. Medusa’s multi-platform presence extends to social media outlets such as X (formerly Twitter) and Telegram, where they regularly communicate updates about their attacks, further amplifying their reach and impact. Their clear web presence, linked to an entity called “OSINT Without Borders,” is highly unusual for ransomware operators.

Medusa operates as a ransomware-as-a-service (RaaS) enterprise, allowing affiliates to conduct attacks in exchange for a profit-sharing model. Affiliates, often independent hackers, retain a significant portion of the ransom payments, while the Medusa operators take a smaller cut. This structure has enabled Medusa to scale rapidly, targeting industries as varied as healthcare, manufacturing, education, finance, and even government sectors worldwide.

Since 2023, Medusa ransomware group has claimed an increasing number of victims. In 2024, Bitdefender estimates that Medusa could target over 200 organizations, a sharp rise from its 145 victims in 2023. Their opportunistic attacks have spanned across the globe, affecting companies and institutions in the United States, Israel, England, Australia, and many other countries.

Medusa’s operations are not limited to ransomware deployment. The group is linked to an OSINT (Open-Source Intelligence) platform under the alias “OSINT Without Borders,” which posts detailed information on data breaches, hacker activities, and even downloadable content related to their leaks. While Medusa attempts to present OSINT Without Borders as a separate entity, cybersecurity analysts have uncovered multiple connections between the two, including shared Telegram channels and overlapping content. This linkage points to a sophisticated, multi-faceted strategy for both intelligence gathering and public relations.

The surface web site run by “OSINT Without Borders” even provides disclaimers distancing itself from illegal activity, despite the frequent references to Medusa’s exploits. This blurring of lines between OSINT and ransomware activities makes Medusa a particularly dangerous and unpredictable adversary.

Medusa’s ransomware attacks typically begin by exploiting known vulnerabilities. One notable example is their exploitation of the CVE-2023-48788, a SQL injection vulnerability in Fortinet’s EMS system. Once inside the network, Medusa deploys tools such as webshells to gain persistence and facilitate data exfiltration. The group is known to use remote management tools like ConnectWise and AnyDesk, often whitelisted by companies, to evade detection.

Medusa’s execution phase involves launching ransomware that encrypts key files using asymmetric RSA encryption, with the encrypted files tagged by the extensions .medusa or .mylock. While the majority of file types are encrypted, Medusa excludes critical system files to ensure the victim’s systems remain functional enough to read the ransom note and negotiate payment.

To defend against Medusa’s attacks, organizations must be proactive in patching known vulnerabilities, especially those related to remote management systems and SQL injection flaws. Monitoring suspicious network activity, particularly around third-party tools like ConnectWise, AnyDesk, and bitsadmin, can also provide early warning signs of compromise.

Furthermore, businesses must educate employees on the dangers of ransomware, establish robust backup protocols, and implement advanced endpoint detection and response (EDR) solutions. While Medusa’s operators have demonstrated a high level of technical prowess, their public-facing nature may also serve as a weak point for security teams to exploit.